Insights from an Informal Educator on the NGSS Journey – Part 2: The Process

This is the second in a series of blog posts by Seth Derner, educational consultant for the American Farm Bureau Foundation for Agriculture. Derner will document the experience of learning how to develop science curriculum materials that meet standards for earning an NGSS Design Badge.

The following is the second in a series of blog posts by Seth Derner, educational consultant for the American Farm Bureau Foundation for Agriculture. Derner will document the experience of learning how to develop science curriculum materials that meet standards for earning an NGSS Design Badge. All photos featured were taken by Derner.

Success on any project requires the right people, the right plan, and the right resources. Developing high-quality curriculum resources for science classrooms is no exception to this adage as we’ve learned in our first year of effort to develop two units of curriculum to submit for NGSS Design Badge review. As informal educators for the American Farm Bureau Foundation for Agriculture, we have a depth of experience in designing educational activities, supporting educational tools and resources, and professional development experiences that require effective planning, quality design, and engaging the right people to develop and field test. But developing to the standards of NGSS takes this all to a whole new level.

Going into this process, we wanted to do it right. We heard loud and clear from the science education community that a lot of resources were being created that claimed to be NGSS, but few actually met the parameters required to truly embrace the multi-dimensional aspect of the NGSS Framework. It became evident to us that we needed to strategically think through three areas to complete this endeavor as follows:

- Engaging the Right People

- Utilizing the Right Resources

- Implementing the Right Plan

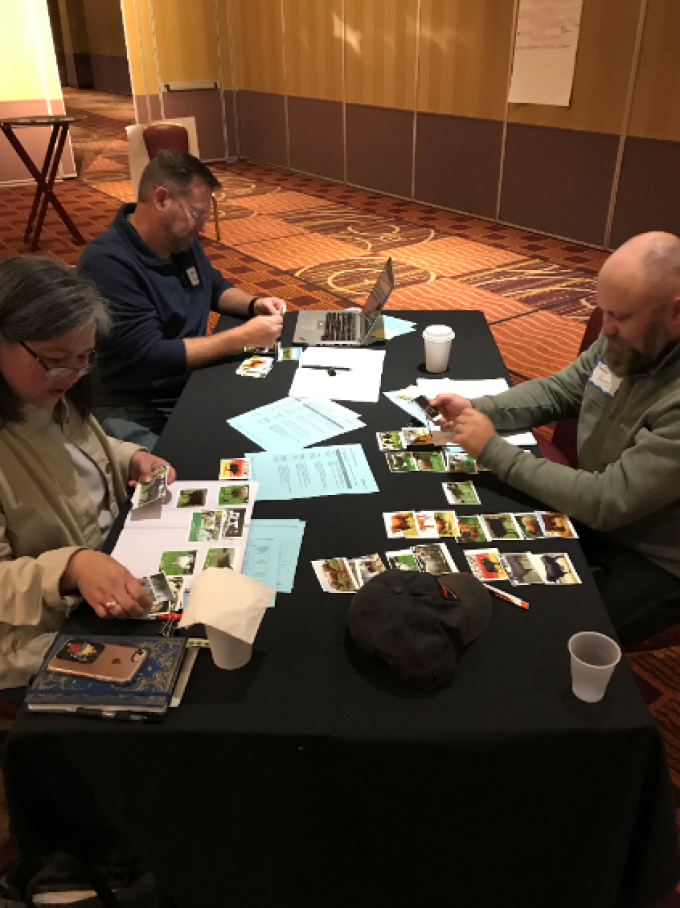

Engaging the right people meant that we sought practicing science educators to design and write the units. The only prerequisite was that our team of teacher-writers had strong science content knowledge and the desire to learn and apply a new NGSS process of curriculum writing called a Storyline. To support the writer teams, we also brought in people who would be team stewards and help coach and manage the moving parts of a team that would do most of the writing in different parts of the country.

Utilizing the right resources meant we needed to engage our writers with subject matter experts who intimately knew the science the units would be written about, the Storylines approach of NGSS unit development, and experts in the NGSS EQuiP Rubric and 3-Dimensional assessment. We did not know the phenomena that would become the focus of the units but knew it would be related to the science found in the practice of beef cattle farming and ranching. We reached out to a scientist at the USDA Agricultural Research Service who is an expert in rangeland management, along with experts in beef science in the Animal Science Department at the University of Nebraska Lincoln. Both entities were excited to engage with this process. So, we had our beef science subject matter experts! Simultaneously, we met with the NextGen Storylines team at Northwestern University to learn more about the Storylines process and figure out how to partner with their team to train our teacher-writers and team stewards. We then went to Achieve, the entity that awards the NGSS Badge, to gain insight on how to submit the units of instruction to be scored. We learned that Achieve provided training on the EQuiP rubric that is used to guide the development of NGSS units and for the development of 3-Dimensional Assessments that are required in the curriculum.

To implement the right plan, we combined the information we learned from Northwestern and Achieve with our previous experience in educational resource development to set up a high potential for success in earning the NGSS Badge. The plan came down to eight distinct experiences in this order:

- National call for and selection of teacher-writers

- Teachers selected to work in either a high school or middle school unit development cohort.

- In-person training one

- An immersive nine-day training that included field experiences with the subject matter experts at USDA ARS and UNL to learn the science in production agriculture. And a deep dive into the Storylines approach of NGSS unit development by the team at Northwestern University.

- Unit architecting

- Over a period of two months, the teacher-writers continued to meet as a cohort with the team steward to create the Storyline architecture, which included identifying the phenomena and flow of potential lessons.

- In-person training two

- All teacher-writers were brought back together for a five-day training where we worked with Achieve for training in using the EQuiP rubric to guide unit development to meet the NGSS requirements. The second half of this training from Achieve focused on the development of 3-Dimensional assessment and Transfer Tasks.

- Unit development

- Cohorts continued development for the next six months. Each cohort managed their own time with the guidance and occasional follow up from the team steward.

- Achieve Feedback

- The initial units were submitted to Achieve to be scored as a feedback review. This review provided us valuable insights of the units and gave us scores compared to the EQuiP rubric so we could focus our attention on pieces of the units that needed revisions.

- Student Pilot

- Authentic student feedback and evidence was always a crucial step in our process. We learned that early on when engaging the Storylines team at Northwestern University. The fall of 2020 we held an institute to train thirteen teachers and five science administrators in the Storylines process of teaching and then asked the teachers to pilot the units of instruction and provide student samples and teacher feedback as we considered revisions to strengthen the units. As valuable as the Achieve review was, we wanted to know these units would stand up to the true test of classroom application!

- Editing and final design/layout support

- The feedback we received from teachers who piloted the units and from Achieve was great, both in amount and insight. All feedback was considered, and a new teacher-writer team and team steward were engaged to make edits. We chose to bring in new teacher-writers at this point based on the specific editing needs identified in the feedback. This allowed us to ask writers to take specific roles to review, edit and finalize aspects across the entire unit of instruction.

- Final Submission for the NGSS Badge

- To Be Determined…. Tune into Part 3 to see how this ends!

After 16 months of development and revisions, we believe we’ve created some great resources for science educators that are high-quality, agriculture-based, and designed-for-NGSS. Our experience has led us to a set of insights of an informal educator venturing into science curriculum development and here is what we’ve learned to date:

Insight #1: Aligning to NGSS is not enough (see previous blog here for more on this insight).

Insight #2: Getting the right phenomenon as the basis of a unit is not for the faint of heart. The phenomenon is the anchor to a scientific concept that drives the entire experience students will have. It must drive students to ask questions about what they are observing and lead to further questions as students begin to learn about what is scientifically happening. What we as adults think is a logical sequence of questions may not always be the same as what middle and high school students think!

Insight #3: It’s more than having the science content right. NGSS demands a 3-Dimensional approach that blends the practices of how scientists work and think. This is paired with crosscutting concepts that apply to all domains of science, for example patterns, to help the learner interpret and make sense of science in the world. Also interweaved is an age appropriate core idea. To be a core idea it should ideally have broad scientific importance, provide tools for understanding more complex science, is interesting to those learning, and is teachable and learnable spanning multiple ages.